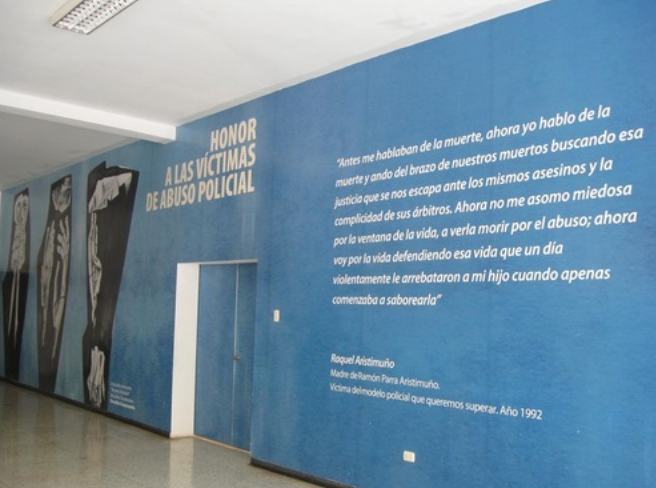

The mural above–dedicated to the victims of police abuse–adorns a main wall of the new civilian-run policing university in Caracas, carrying with it a quote by Raquel Aristimuño, whose son was killed by the police here in 1992. The mural serves as a reminder of the violent and abusive history that the police must overcome if they are to convince Venezuelans that security forces are no longer “criminals in uniform” (malandros uniformados).

Before the passage of the 2008 Organic Law of the Police Service and of the National Police Body, police training was left in the hands of the National Guard, which resulted in little differentiation between tactics utilized by the military and the police. Police officers trained according to a military model of security have tended to view civilians (especially young males from the lower classes) as a suspicious enemy to be subdued, a mentality that has led to thousands of civilian deaths at the hands of the police each year. Indeed, homicide rates in Venezuela would be around 20% higher if the killings carried out by police officers—listed under “resistance to authority”— were counted as homicides. According to Provea, 3,492 killings in 2010 were placed in this category, which would represent an almost 300% increase from the early 2000s.

An important move away from this militarized approach to policing was included in the 2008 reform, which placed training in civilian hands: the National Experimental University of Security ( la Universidad Nacional Experimental de la Seguridad, UNES). UNES is Venezuela’s first experience with a civilian-run policing university, and is headed up by human rights activists like Soraya El Achkar (also the Executive Secretary of the General Police Council) and Antonio Gonzalez Plessman.

UNES’s curriculum places a heavy emphasis on human rights training and conflict mediation. Additionally, police officers are now trained according to a model of “progressive and differential use of force.” This training teaches officers that the amount of force used by the officer must depend on the actions taken by the person the officer is engaging. The idea is that there are a number of strategies from which officers may draw in dealing with civilians. In the new civilian model lethal force is “defensive,” to be used as a last resort only when a suspect’s actions are putting someone else’s life in danger.

The importance of these changes can hardly be overemphasized. In the previous military model, use of force was based on the idea of “shoot first, ask questions later,” and it was considered entirely appropriate for a police officer to shoot at an unarmed, fleeing suspect. Of course, implementing these norms is an uphill battle as military concepts of the use of force still predominate among many officers and civilians.

UNES currently trains all officers in the National Bolivarian Police (PNB) and will eventually be charged with training officers affiliated with any police body in the country. UNES has three locations in Caracas (Catia, El Helicoide in San Agustín and El Junquito; the latter two are where most officer training takes place) and has opened five other university sites outside of the city (in the states of Anzoátegui, Aragua-Carabobo, Lara, Tachira, and Zulia).

All of the university’s locations in Caracas have important symbolic histories that highlight the context in which UNES’ model is being implemented. The location in Catia was built on the former site of El Retén de Catia, an infamous prison demolished in 1997 that was widely recognized for the violence, corruption, and human rights abuses that went on within its walls. UNES took over the site in San Agustín in 2010, which was built by Venezuela’s last dictator and where many Venezuelans tell stories of the the national intelligence police (formerly DISIP now SEBIN) holding and torturing civilians. Lastly, the location in El Junquito used to be one of the National Guard’s training sites for the police before the reform.

At the end of 2011 UNES reported graduating 23,714 officers and aims to graduate 20,000 more this year. Though, not all of these officers are destined for the PNB; many will work in municipal and state police forces. Basic training for police officers lasts for at least one year. And, once they have graduated, officers are required to take yearly refresher courses at UNES. Bachelor and graduate degrees are also offered by the university and required if an officer wants to move up in rank.

In June 2012 UNES announced it would begin the process of retraining and professionalizing the 90,000 police officers that make up the 100 plus police agencies in the country. This will certainly be a mayor challenge for UNES, as this retraining adds tens of thousands of new students to its current enrollment. It will also present UNES with the sticky issue of attempting to retrain officers—many of whom have served for over 15 years—under a drastically different model of policing from the one they learned at the beginning of their careers. However UNES has done this before. It started in 2009 by training those Metropolitan Police officers that were selected to become part of the PNB. Apart from training police officers, the university has also taken over the training of firemen and women, prison personnel, the Venezuelan criminal investigations force (the CICPC, Cuerpo de Investigaciones Científicas, Penales y Criminalísticas) and disaster response units.

UNES is divided into a number of departments, dedicated not only to training police officers but also to conducting research and investigations, engaging in community outreach, and promoting citizen participation. Apart from its more traditional university functions, UNES sends teams into lower-class sectors of the city to organize health workshops, children’s events, and give presentations on conflict resolution and mediation. With a focus on the recuperation of public space, UNES funded a round of salsa concerts over a three-month period in a central shopping strip in Catia, a group of working-class barrios in Caracas, with the goal of “taking back” public space in the area. Information on UNES’ social outreach programs and community collaboration is published in the Revista ComUNES, which is available online, as are previous investigations that the university has published.

In the next post, we will look at some of the tensions between the preventative citizen-oriented security model being put forth by institutions like UNES and the CGP (see our previous post) and the continued reliance upon militarized security tactics. These tensions have created obstacles that the reform will have to overcome if this new model is to become dominant.