For the third time since the death of Hugo Chávez’s death Venezuelans are going to the polls. But in contrast to any previous elections, Chavismo is facing the electoral event with the numbers against it. The latest numbers from Datanálisis suggest the government has slid even further to approximately 22%, with over 75% rejecting its performance. These would be troubling numbers for any incumbent.

In such a situation it is not surprising that the Venezuelan government has paid increasing attention to a nationalist rhetoric that goes from defending the Esequibo against Guyana to closing the border with Colombia. Such tactics are predicted in theories of political science (see my previous post on diversionary theory as well as (Tavits & Potter 2015; Solt 2011; Pardos-Sagarzazu 2015; Vavrek 2009). However, in bad economic times there isn’t much the government can do to divert attention as citizens can see the economic reality (Pardos-Prado & Sagarzazu, 2014). And in Venezeula that economic reality is grim indeed.

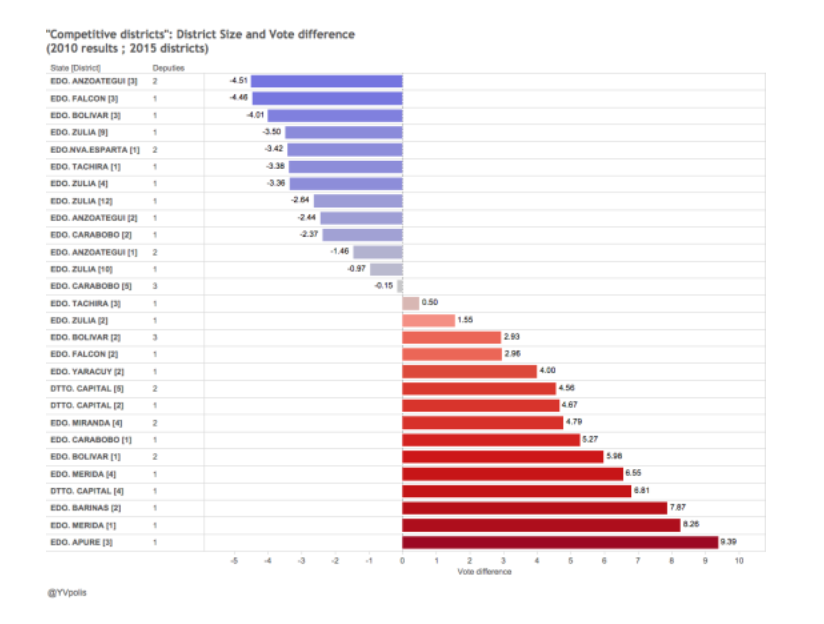

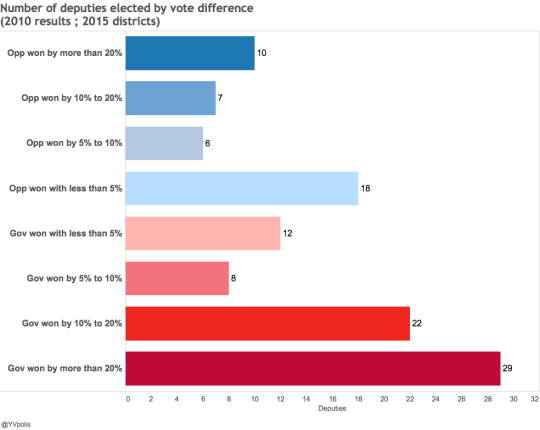

Using the 2010 results on the 2015 districts we can identify 8 districts where the government has a margin of less than 5% (see figure 1). These 8 districts elect 12 deputies elected. Furthermore there are 7 more districts that elect 8 deputies where the government has a margin between 5% and 10%. That means that with a 10% swing in favor of the opposition (opo 59% vs gov’t 40%) -and a uniform swing across- the opposition could reach 61 deputies elected nominally. Since we elect another 54 between state representatives (51) and indigenous representatives (3), with half of those (27) the opposition passes the 84 deputy threshold and to reach to a magic number of 88 deputies.

So, can the opposition win in vote share and in seat share the legislative elections in December? Yes they can. Will it be easy? Not necessarily.

First, it is important to remember that in the upcoming legislative election Venezuelans won’t just be aggregating the votes into a grand total to see who won. The parliamentary election has a complicated map and a strong territorial bias that favors the rural areas, and thus the government.

Second, while the polls show that around 75% reject the government’s job only a little over half approve of the job the opposition is doing. Hence there are people who criticize the government but still don’t side with the opposition.

It is true that since the last election the pro-government camp has lost almost half of its supporters (38% to 22%), and the opposition has seen a slightly larger increase (26% to 45%). But there is no information as to where this support is coming from, and giving the typical pattern of raising support for emerging parties and the spread of parties in Venezuela (Sagarzazu, 2011) it is highly likely that most of this increase is seen in heavily urban rather than rural areas.

Third, polls are showing that despite the crisis government supporters are more likely to vote than opposition supporters. This is not surprising as it is usually the case, the exception to this rule was the 2007 Referendum where the opposition won partly due to a low turnout in the government’s ranks. Even lower than both government (75%) and opposition (66%) turnout figures is that of the Independents (Ni-Ni’s) (only 30% are likely to vote).

Finally, the latest Datanálisis poll also shows that the capacity of mobilization of the government (86%) is almost twice as that of the opposition (47%). This is quite telling because it shows that those who support the government are much more consistent than those who support the opposition.

In sum, the election results will depend on several factors:

1) Where is the opposition making inroads? Is it only securing what already has or is it also diminishing the lead in heavy pro-government districts?

2) How do voters mobilize? Do opposition/government voters turnout at high rates or is there a non-uniform participation?

3) What do the disgruntled government supporters turned Ni-Ni’s do? Do they abstain? Do they vote for the government or the opposition?

Opposition leaders and followers need to be aware of these ground-level challenges because it is entirely possible that they win the election in votes but not in seats, and that could lead opposition radicals to push for non-electoral paths to power.

Dr. Iñaki Sagarzazu is a lecturer in comparative politics at the University of Glasgow.