On October 7 ballots were cast in Venezuela’s presidential elections without notable disruptions. Citizens arrived early at the polling centers, most of which were promptly installed and functioned as planned. According to the second report of October 8th by the Observatorio Electoral Venezolano, the few violent events that did take place were not significant. Election Day ended peacefully, contributing to a quick announcement of the first results by the electoral authority, and to a prompt concession by the losing candidate. President Chávez won with 8,185,120 votes, while Capriles Radonski received 6,583,426 votes. As in the 2006 presidential elections the two leading contenders together received more than 99% of the votes. The remaining four candidates only received 0.67%.

It is important to note that Venezuelans participated in massive numbers in this election, with more than 80.52% of the electorate voting–the highest turnout in the Chávez era. Two readings can be given of this figure. On the one hand, this turnout suggests citizens’ positive appraisal of voting and that they continue to view the electoral process as a credible and efficient tool for the selection of the highest authorities of the country. The National Electoral Council’s (CNE) insistence on extensive auditing of the different components of the electoral system’s platform weeks before the election, as well as insistence on auditing by the representatives of both campaigns, undoubtedly contributed to citizens’ confidence.

But a second reading is less positive and is related to political polarization. A lot has been written on the fractured character of Venezuelan society in the past two decades, and the inability of its citizens to achieve a basic consensus on the road ahead for the country. At one time the 1999 Constitution seemed to offer a beginning for common agreements, but latter events frustrated such hopes. High voting participation is, then, the manifestation of the majority’s perspective that in every electoral event the future is at stake. Candidates’ proposals are not presented as varying in emphasis or as a difference in tone, but as antagonistic and mutually exclusive.

In national terms, forces are now more balanced. In the presidential elections of 2006, President Chávez won with 62.8% of the votes and his contender Manuel Rosales only received 36.9%. The 2012 percentages ended 55.1% to 44.3%, with the difference being reduced from 26 to 11 points. If one considers the “ventajismo” (incumbents advantage) that has favored Chávez, this reduction is very significant. In net numbers Chávez increased his votes only modestly when compared with the opposition (876,040 votes increase for Chávez, 2,290,960 for the opposition).

It became evident that the majority supports the President, but also that a very significant minority (45%) opposes him. The majority seems willing to advance towards a “communal state” that does not contemplate political pluralism. But a large minority demands such pluralism. If this is the balance of forces, the electoral mechanism does not seem to have provided the government with enough of a mandate to impose the communal state on the country. It is likely that the government expects an increase in its share of votes in the governors elections in December of this year. If this happens, the government will most likely forge ahead without engaging in dialogue with the opposition. For now it has at least acknowledged that channels for unity must be opened. For example, after the elections Chávez phoned Capriles and for the first time called him by his real name (Globovisión en Noticias24, 8-10-2012).

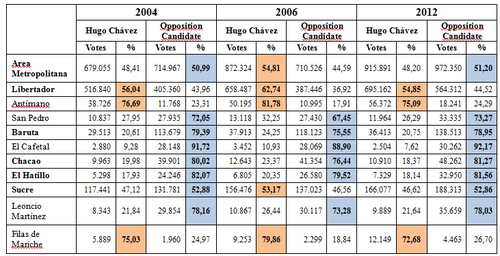

The October 7 results show that Venezuela’s political polarization persists and has remained constant territorially and by income level since 1998. In the poorer areas of the population, Chávez wins, and in middle and high-class areas the opposition wins. This can be seen in the following chart of electoral results from the Metropolitan Area of Caracas. The same results could be tabulated for any city of the country:

Table 1: Metropolitan Area of Caracas: Election Results for 2004, 2006, 2012

As can be seen, since the 2004 elections in the capital have been very close. Of these three elections, Chávez won once and the opposition twice. But if we scrutinize the results of the five municipalities more closely, we discover that in several of them the results were not so close and were more or less stable. In Libertador municipality, where most of the population is poor, Chávez has always been victorious, while in Baruta, Chacao, and El Hatillo, mostly middle and high class areas, he has always lost. Only Sucre municipality has varied: The opposition has won twice and Chávez once. If we look at the parish level, this socio-economic pattern of voting becomes even clearer. The “richest” parish of Libertador, San Pedro, always votes for the opposition (73.3% in the most recent election), but the poorest, Antímano, always votes for Chávez (75.1%). This is also the case in Sucre: even if as a municipality it fluctuates, at the parish level it is consistent. In Leoncio Martínez, the richest parish of the municipality, Chávez has always suffered overwhelming defeats: 78% of voters voted against him this time around. But in Filas de Mariche, a poor area, the results are always the opposite, with 72.7% supporting Chávez in the most recent election. The parish El Cafetal of Baruta, a middle-class area, is the most radical example of territorial polarization: The opposition always wins in El Cafetal with over 85% of the votes, and this time it won with 92.2% of the vote!

This territorial polarization is not only seen in Caracas. If we look at the electoral results of any other city we will witness the same phenomenon. In Maracaibo, votes for Chávez in the poor parish of Ildefonso Martínez reached 62.2%, but in rich Olegario Villalobos Capriles reached 77.6%. In Ciudad Guayana, in the Caroní municipality of Bolívar State, in parish of Della Costa, Chavez won with 62.7% and in the parish of Universidad Capriles won with 76.9%. In the Iribarren municipality, in the city of Barquisimeto, in Parish Unión Chávez won with 56.5%, while in Santa Rosa Capriles won with 66.9%. In the city of Valencia, Carabobo State, in Santa Rosa Chávez won with 58.1% and in San José Capriles won with 87.8%. Similar results can be observed in practically every city and region of the country. Venezuelan’s electoral preferences seem to be strongly determined by socio-economic conditions. This is perhaps an important ingredient in understanding why so many people were convinced that the results of the October 7 elections would result in an outcome different from what they did. People tend to relate to others in relatively homogeneous socio-economic environments, in which the majority express similar electoral preferences, and tend to mistakenly identify their surroundings as representative of the whole country.

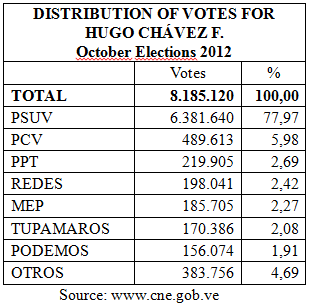

The October 7 results also show some changes inside both dominant electoral blocks. In the pro-government block, despite President Chavez’s efforts, the PSUV has not become the unified party of the chavista forces that Chávez has hoped for, founding the party in 2007 with that explicit purpose in mind. Without a doubt the PSUV is the main party supporting the President, but without the votes of the rest of the parties of the Gran Polo Patriótico, the incumbent would have been in trouble.

Of the votes for Chávez, 22% were cast for parties other than the PSUV. These other parties contributed up to 1,803,480 votes, which were crucial for the President’s victory over Capriles. These parties have become the vehicles for expressing discontent with, and even rejection of, the PSUV. They seem to vindicate, inside the chavista forces, the need for diversity and pluralism, so often absent from the internal dynamics of the government and its party.

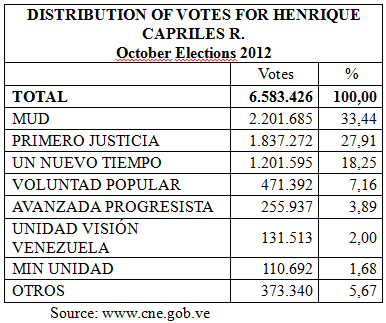

Changes were also evident inside the opposition block. The MUD option obtained the most votes for Capriles. It was a new option that clearly expressed the demand for unity. Several important historical parties (AD, COPEI, MAS, LCR) called on their sympathizers to vote for the MUD option and did not put their own parties on the ballot. The MUD option was also useful to gather votes from opposition sympathizers with anti-politics stances that did not support any party. The party that has now emerged as the main opposition party is Primero Justicia, which increased its votes since 2006 by 537,723 votes, a 41.4% growth. In 2006 the most voted party was Un Nuevo Tiempo, which witnessed a reduction in votes by 353,767, slipping to third place within the opposition in terms of votes received. Of course this might simply be a result of the fact that the opposition candidate in 2006 came from that party, while Capriles came from Primero Justicia.

Margarita Lopez Maya is a historian at the Universidad Central de Venezuela. Luis E Lander is one of the the directors of the Observatorio Electoral Venezolano.

(Translated by Hugo Pérez Hernaíz and Rebecca Hanson)