This morning, the New York Times reported that Venezuelan military officers attempting to organize a coup requested a meeting with the Trump Administration, and that the White House designated a career diplomat to meet with the coup plotters several times from late 2017 to earlier this year. According to the investigation, a former military commander requested that the U.S. government supply him and his conspirators with encrypted radios. The unnamed American diplomat–who reportedly wasn’t authorized to negotiate anything of substance–passed the request on, but ultimately Washington refused to provide material aid. The NYT also reports that, even after a third meeting earlier in 2018, the conversations “did not result in a promise of material aid or even a clear signal that Washington endorsed the rebels’ plans, according to the Venezuelan commander and several American officials.”

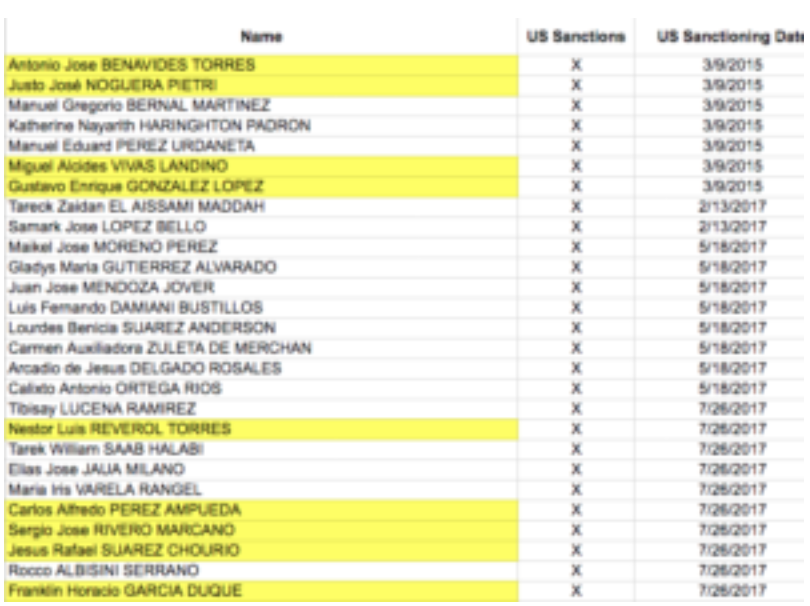

The Times did not identify the plotters, but did say that one of them was a “former military commander” who has been sanctioned by the U.S. government for corruption. This does not narrow the field by much. In our WOLA Targeted Sanctions Database, I have highlighted the names in yellow that meet this description, assuming “former commander” is broadly defined as any onetime commanding officer of an armed forces unit. By my count there are at least 23 individuals who fit that description, although we can safely say that some of them–like Diosdado Cabello–seem to be unlikely suspects.

Ultimately, the fact that the U.S. government met with this sanctioned official is also evidence of communication with targeted individuals, which is necessary in order for the sanctions to minimize the chance of “hardening” support for the Maduro government. It’s also quite possible that this individual was sanctioned by the previous administration. This is the case, for instance, of Major General Clíver Alcalá Cordones, who has spoken out against Maduro in recent months but was sanctioned in 2011. As we’ve pointed out, the Trump administration appears to be avoiding sanctions against individuals that are still active in the security forces (broadly defined as military, intelligence agencies, and police). Just 11 of 64 (17%) individuals sanctioned under Trump were active in security forces at the time of their sanctioning, compared with five out of seven (71%) under Obama. This is in line with the fact that this White House places a greater emphasis on the security forces playing a role in some kind of transition.

See the complete Venezuela Targeted Sanctions Database here.

(Note: Sheet 1 is post-E.O. 13692, and Sheet 2 is pre-E.O. 13692)

It’s also worth nothing that we already knew some of this story from previous reporting. The Wall Street Journal reported several months ago that Maduro government dismantled a coup planned for March, arresting Major General Miguel Rodríguez Torres and some armored battalion commanders for attempted insurrection. Bloomberg subsequently reported that another attempted coup was broken up just before the May 20 election. The latter story also alleged that “Colombian and U.S. officials, who allegedly knew about the plot and winked from the sidelines, declined to provide active support.”

But the New York Times appears to be the first to get confirmation from the United States government that it met with the coup plotters. The report also suggests that the same group was behind both the March and May plots, but not the failed drone attack last month. Exactly why the U.S. declined to offer material support is not clear, although the NYT notes that the American diplomat conveyed that the Venezuelan conspirators did not seem to have a detailed plan. Instead they appeared to be looking to the U.S. government for ideas and guidance. While the White House has framed these meetings as part of a “dialogue with all Venezuelans who demonstrate a desire for democracy,” it is possible that the Trump administration simply saw this plot as inviable.

Moving forward, this story is bound to make waves. In the United States, it is likely to fuel outcry from the most hawkish sectors who will claim that these attempts failed because the U.S. didn’t offer needed support. This is particularly concerning at a time when a recent shuffling at the National Security Council suggests these sectors increasingly have the White House’s ear on Venezuela policy.

This is bad news, because as we have said on various occasions, a military coup would be highly unpredictable, and would absolutely not guarantee a return to electoral democracy. In Latin America the confirmation that these meetings occurred could also endanger the regional consensus on Venezuela’s authoritarian slide among the 14-member Lima Group, as Latin American nations have been sensitive to sovereignty concerns in responding to the crisis. In Venezuela, the news allows Maduro to bolster his claim that he is under siege from imperialist forces, a claim that he has used to justify a crackdown on both the traditional opposition and within the armed forces. Additionally, evidence of the U.S. flirting with a coup or other “military option” on Venezuela creates harmful disincentives for an already badly organized and bitterly divided opposition. Instead of encouraging opposition leaders to unite behind a single platform, agenda, and leadership structure, it gives the impression that they can somehow avoid having to do the hard work because the country will be delivered to them through U.S. intervention in some form.