In recent weeks, two countries joined the growing number of nations that have applied targeted sanctions against government officials and elites in Venezuela. On March 27, Panama announced sanctions that restrict economic activity with 55 Venezuelan officials (and 16 companies). The following day, Switzerland announced that it would be joining the European Union in applying the E.U. sanctions against seven officials, freezing their assets and denying them visas, as well as adhering to the E.U. ban on transferring arms or law enforcement material used for internal repression to Venezuela.

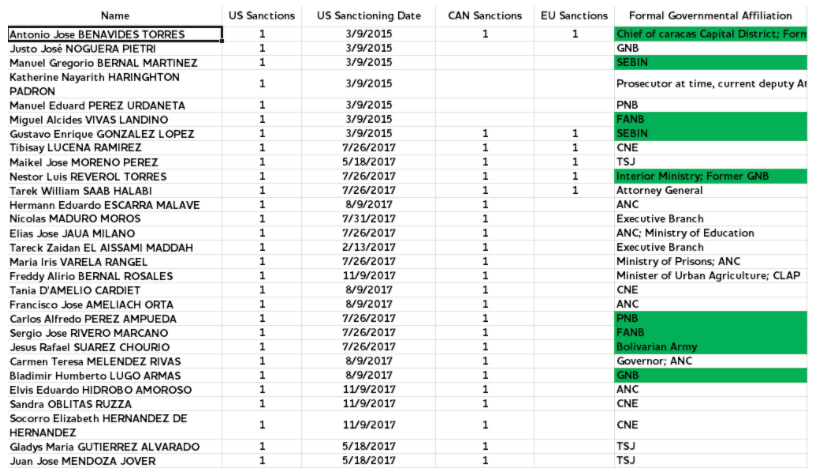

In light of this, we have updated our public database mapping targeted sanctions so far, which also lists the sanctions leveled by the E.U. and by the U.S. and Canadian governments, and provides context on the officials’ current affiliation and background in the Maduro government. On the U.S. list, it is worth mentioning that we have separated out the 57 Venezuelan officials and prominent figures sanctioned since the Obama administration’s March 2015 executive order set in motion the use of targeted sanctions as a political pressure tool. Because of this, our tally of U.S. sanctions may differ from those provided by other groups, which include other sanctions announced from 2008 to 2013 (we’ve listed these in a separate sheet on the database).

See: Venezuela Targeted Sanctions Database

The March 27 and 28 developments are significant for a variety of reasons. First, the Swiss and Panamanian actions make the targeted sanctions more multilateral in nature, which academic literature on sanctions regimes suggests could make them more effective. It also makes Panama the first Latin American nation—and the first of the 14 Lima Group countries—to join in the international sanctions regime in response to Venezuela’s crisis.

While other countries in the region, like Mexico and Colombia, have issued statements in support of U.S. targeted sanctions, before Panama no Latin American country had joined in applying them. This may change in the coming weeks, as the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is reportedly offering the assistance of legal and policy experts to regional governments to encourage them to adopt reforms that allow them to apply their own targeted sanctions regimes. In Panama’s case, neither the Ministry of Economy and Finance’s announcement of the sanctions nor the legal resolution outlining the measures in the Gaceta Oficial mention human rights violations or rule of law issues, instead citing Panama’s international anti-money laundering commitments and targeted officials’ “high risk in money laundering, financing of terrorism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.”

Panama’s announcement may be a sign that other Latin American countries could join in applying sanctions in the future, and this does not appear to be lost on Venezuelan officials. Evidence of this can be seen in the fact that the official government response to the Panamanian sanctions was far more severe than the response to the Swiss sanctions. Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza merely sent a formal note of protest to the Swiss embassy in response to the European government’s announcement. By contrast, Venezuela reacted to the Panamanian sanctions by withdrawing its ambassador and ordering the suspension of economic relations with 22 Panamanian officials (including the country’s president and vice president) and 46 companies—among them Copa Airlines—for a period of 90 days.

The scale of this response echoes Venezuela’s decision to cut diplomatic ties with Spain in January 2018 in the aftermath of the E.U. sanctions. However, on April 18 the two countries signed a deal to restore diplomatic relations. This suggests that the current clash with Panama may not be permanent either, but intended as a signal to other regional governments weighing whether or not to adopt sanctions (April 27 update: as predicted, the diplomatic spat with Panama proved short-lived, with both countries announcing on April 26 that they would restore ambassadors and resume “aerial connectivity,” presumably a reference to Copa. The fate of the other 45 companies is unclear, but both countries’ foreign ministers resolved to submit a report on bilateral relations in 30 days).

The latest round of sanctions contains a few other interesting features that bear deeper analysis. Among them:

- While the Swiss government fully adopted the same sanctions list as the E.U. (including the arms and repressive material embargo), the Panamanian sanctions have some notable discrepancies from the U.S. list. Panama, for instance, joins Canada, the E.U. and now Switzerland in sanctioning Diosdado Cabello. To date, the U.S. government has refrained from imposing sanctions against Cabello.

- Panama did not sanction Vice President Tareck El Aissami, who has been accused by the United States of benefiting from an illegal drug shipment to the United States. Panama also refrained from sanctioning Samark Bello Lopez, the alleged frontman in the case of the shipment linked to El AIssami.

- Apart from Cabello, the Panamanian government includes one other name not on the U.S. sanctions list: that of Argenis Chavez, younger brother of the late Hugo Chavez and Governor of Barinas state. So far, Argenis Chavez had only been on the Canadian list. He is the only figure to be sanctioned exclusively by Panama and Canada, and not by any other country.

- It is also noteworthy that both Switzerland and Panama have significant reputations as international money laundering hubs. The fact that they announced sanctions against Venezuelan officials in the same week sends a message: that officials in Venezuela may face an increasingly difficult time securing assets abroad, even in countries with traditionally more permissive approaches to banking.

As with all existing targeted sanctions, the impact of these measures will likely depend on a variety of factors. As we have noted, targeted sanctions may have a complicated net impact on Venezuelan government officials: they raise exit costs for officials that have been named, reducing their travel options and cutting into any assets abroad, while in turn providing lowered incentives to break from the government unless the implementation of sanctions is accompanied by a communications strategy that lays out what steps targeted officials can take to remove themselves from the list. We have argued that these exit costs, or “costs of moderation,” often outweigh the costs of continued repression for many officials.

At the same time, proponents of targeted sanctions claim that the targeted sanctions have a “signaling” effect on those who have not yet been named. They point to the case of former Attorney General Luisa Ortega as a justification for this strategy, claiming that pressure from U.S. political actors like Marco Rubio to add her to the sanctions list was a factor in her decision to break from Maduro. This is presumably the logic behind the decision of the U.S. government to so far refrain from sanctioning key actors like Diosdado Cabello, the Rodriguez siblings, or Vladimir Padrino Lopez.

Under the logic of both arguments, however, there is an important point of overlap: the importance of prioritizing multilateral over unilateral sanctions. The more multilateral sanctions become, they become more effective insofar as they actually increase the costs of repression (by showing that officials’ assets could be at risk in a growing number of countries if repression continues), as well as generating signaling effects (by stoking concerns among officials not yet named, or those who have been named on some countries’ sanctions lists but not others). And of course, multilateral sanctions are more strategic in their ability to subvert the antiimperialist rhetoric of the Maduro government, showing that there is actually broad coalition of countries that oppose the current situation in Venezuela.

Note: Special thanks so WOLA Venezuela Program intern Melissa Medina-Marquez for her help in updating the sanctions database.