Figure produced by FUNDEPRO, charting the deaths of security forces in Venezuela from 2012-2015 (published here)

One morning in October 2013 I was sitting in the office of Education Coordination at the Police University (Universidad Nacional Experimental de la Seguridad) with Alexis, a National Bolivarian Police officer and professor at the university. We were chatting about some parts that Alexis needed for a car that he owned, in the event that he needed to sell it, when Rosa, another professor and Alexis’ officemate, burst in, looking frazzled and rushed.

She had a basket in her arms that contained small arepas wrapped in cloth and a block of cheese. In a frustrated voice, she asked Alexis what he had brought to contribute to the get together they were having that day. Laughing and shrugging his shoulders, he said he had not brought anything.

Rosa rolled her eyes and looked at me, explaining in an exasperated voice that they were having a get together that day for Tomás, a friend and fellow officer who had recently recovered from being shot while off duty. Alexis remarked that Tomás had been stupid, leaving the department in uniform. Rosa agreed and said that he was probably shot for the gun he didn’t have on him (National Police officers are required to check their guns in when their shift is over).

With a look of awe on her face she said he had been fired at eighteen times. “They didn’t shoot at him 18 times to rob him. These were criminals looking to pick up a new gun,” she said. Alexis and Rosa agreed that officers themselves are partly to blame for getting killed, when they do not take seriously the fact that they are “marked.”

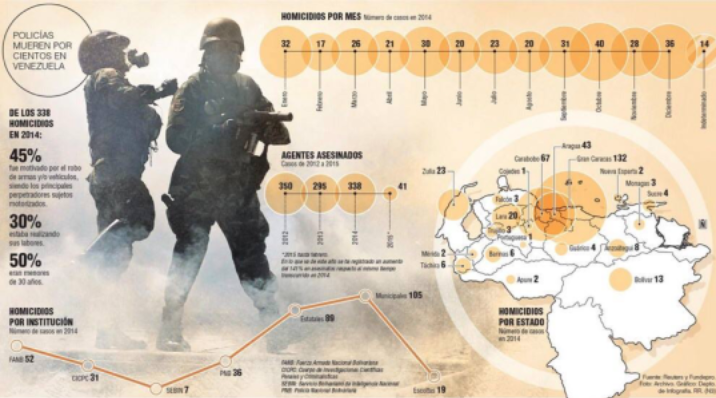

While there are no official figures on the number of police killed each year in Venezuela, the numbers that are available seem to suggest that police homicides are on the rise. The opposition linked NGO Fundación para el Debido Proceso (FUNDEPRO) claims to have counted 295-security officers killed in 2013, 251 in 2014, and 332 in 2015 (this number includes police and military officers as well as private security). According to the PanAm post, 59 police officers were killed in Caracas in 2010; by 2014 this unofficial count had risen to 132.

National and international news have picked up on this trend, publishing articles with headlines like “To Be a Police Officer in Venezuela is to Be Sentenced to Death,” “In Violent Venezuela, Police Killings Surge to Almost One a Day,” “These are the 7 Police Officers that were Killed within 72 Hours in Venezuela” and “Even the Police Cannot Save Themselves from Delinquents.”

Attacks on police and military officers by organized crime, armed with grenades and heavy firearms, have become more common. By September of 2015, the media had already published stories of sixteen direct attacks on police and military stations nationwide. In October 2015 United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) leader Freddy Bernal claimed that the attacks were evidence of the effectiveness of police actions, but President Nicolás Maduro explained them as acts of right-wing terrorism.

The most common narrative about these deaths is that officers are being targeted, often when they are alone, and are killed for their guns. While conducting fieldwork in Venezuela between 2012 and 2014, as the government started promoting disarmament programs and legislation and implementing police reform, I heard this narrative become more and more common.

Even supporters of disarmament and police reform said that these initiatives contributed to police killings. This argument is based on the assumption that disarmament made guns and bullets harder to find, while the reform made it harder for police officers to protect themselves. As a result, gang members and criminals turned to killing officers –weakened by reform – to supplement their access to weapons.

However, there are a few problems with this narrative. First, disarmament might have impeded access to guns and ammunition for a short period of time by shutting down privately owned gun shops. But factions within the government who were against disarmament and the inconsistent and superficial implementation of disarmament legislation kept it from having any long-term impact.

More importantly, most police officers are not dying on the job. In a recent edition of a Venezuelan sociology journal Espacio Abierto, criminologist Keymer Avila suggests that the majority of police murders should not be considered the murder of police officers. He finds that 73 percent of police officers killed in 2013 were not on duty and 67 percent were not in uniform. He suggests that the real problem is Venezuela’s high level of violence, in which police officers are swept up. In other words, they are not being killed in confrontations with gang member or criminal organizations, but are dying like others in the poor areas of town where they live.

Cycles of vengeance between police forces and organized crime do seem to be behind some of the cases of police and supposed criminals killed. Criminologist Andres Antillano suggests that the level of police violence in recent years has led to an increasing level of organization among armed gangs that now see themselves in open conflict with police. But these conflicts have led to a disproportionate number of civilian deaths, not police killings.

The fact that officers are being killed off duty does not mean that this narrative is entirely incorrect. Police officers are often armed, even when they are off duty. And some are probably killed for the weapons they are carrying.

Nevertheless, almost all of the police officers I knew while conducting my research told me that they kept their occupation hidden from neighbors. Many of them left their uniforms at the station so they did not have to leave the house or come home in uniform, making it harder to identify an officer when they are off duty. As Alexis and Rosa suggested, this is exactly why Tomás was shot – because he did not take the proper precautions to hide his occupation.

Whether they die as police or as civilians, news stories and headlines about police deaths carry a certain symbolic weight. What better way to represent the weakness and disorganization of a state or government than to present the state’s coercive arm as impotent and vulnerable? Police killings show criminals to have the upper hand. According to Jackelin Sandoval, director of a Venezuelan NGO called the Due Process Foundation (FUNDEPRO), these cases demonstrate the point criminals have reached. For them killing a person is “not enough.” Instead, they seek to “gain authority…through terror.”

News headlines and stories correctly portray concerns over insecurity and violence, concerns that are prevalent among both citizens and officers. In the minds of officers like Alexis, police are “marked” as targets in a way that citizens are not. Police officers that I worked with felt vulnerable, exposed, and dispensable, both due to increasing violence and steps taken by the government to regulate police use of force. Combined with poor pay and few benefits, officers feel – and in many ways are – economically and physically vulnerable, much like other men in the marginalized sectors of the city where most of them grow up.

That the family of a National Police officer receives a one-time payment of 30,000Bs ($40) from the state when they are killed contributes to feelings of disposability. Nevertheless, this vulnerability stems more from social change (increasing violence) and their class position (as poor men) than their occupation.

While the narrative of officers being “marked” reflects a major problem facing the country, it misidentifies the source. Though it directs attention to increasing violence, it suggests that the source of this problem lies in the weakening of police power, ultimately delegitimizing police reform and disarmament initiatives. It suggests that the world has become ordered and controlled by new actors – whether those are collectives, gangs, or paramilitaries – who the police must be able to react against with more force, more violence, and more weapons.

In short, it demands an increase in state violence. In doing so, it obscures increasing rates of police violence in the country, and neglects the fact that militarized security plans like the Operación Liberación del Pueblo and the Plan Patria Segura have already greatly increased the lethality of the National Guard and certain branches of the police.

Like officers in Brazil, the officers I knew discussed the need for harsher punishment for someone convicted of killing a police officer. However, the implementation of new laws and regulations within the context of a broken criminal justice system, where 98 percent of crimes committed are not prosecuted, might just exacerbate officer’s sense of vulnerability. Because if and when these laws are left unenforced they will provide officers and other observers even more “evidence” that extralegal state violence and mano dura policing are necessary.