In the first two posts in this series (here and here) we looked at incumbent’s advantage and ventajismo as they are present in the office of the presidency, the candidates’ access to media and advertising, and the candidates’ ability to mobilize their followers. In this final post we are going to look at two final issues–the electoral register and independent observation–and give a final assessment.

Electoral Register

One long term policy of the Chávez government has been to expand coverage of identification-without which people are not recognized by the state-as well as voter registration. Indeed the electoral register has grown more than 70%, (from 11 million when Chávez was first elected in 1998 to 19 million) at the same time that the Venezuelan population has only grown 22% (from 23 million to 28 million). This has caused understandable concern among the political opposition that the government might be stacking the RE with ineligible, non-existent or deceased people.

However, as part of its Electoral Monitor project in 2012, a team of Catholic University demographers reviewed the electoral register and concluded that it was trustworthy. They found the growth was explained by increasing coverage and the aging of the population. This latter means a higher percentage of the population is of voting age. See our interview with Anitza Freitez, leader of the audit.

The CNE will use the same RE these elections that it used for the 2012 elections. This decision sparked some controversy because in January and February, the RE had been opened for new voters for the July 14 Municipal Elections (now postponed until reprogrammed by the CNE), incorporating 103,986 new electors. However it had been previously announced that the new RE would not be reviewed, purged and confirmed until April 20.

Observation

Since the 2006 presidential elections the CNE has not invited international observers to Venezuelan elections. From 1998 to 2006 international observers such as the Carter Center, the Organization of American States and the European Union played an important role in ensuring transparent and credible elections. However, arguing on the basis of national sovereignty, in 2007 the CNE moved to a model of international “accompaniment.” In contrast to observers, groups who accompany do not have have independence of movement, access to the electronic voting, and the technical capacity to carryout “quick counts” that can verify the vote tally. As such, accompaniment is largely symbolic. (see Carter Center report pp.24-26)

For the 2012 the CNE invited UNASUR to accompany the election, as well as the Carter Center. The latter declined and instead sent an independent “study mission.” This year they were both invited again and both accepted the accompaniment model.

However, this does not mean there is no independent observation. During the 2012 both the Asamblea de Educación and the Observatorio Electoral Venezolano carried forward independent and technically sophisticated efforts to observe electoral conditions and verify the vote count. Any suggestion that they are not independent can quickly be dispelled by looking at their 2012 reports which included serious criticism (See Asamblea’s report here and OEV’s here). Both are also engaged in observing this election.

In its 2012 report the Carter Center calls the CNE’s policy a move to a “National Stakeholders Model.” They argue that “Domestic observer organizations, first appearing in 2000, grew more experienced and professional; political parties negotiated ever-increasing participation in pre- and postelection audits of the automated voting system as well as providing party poll watchers on election day; NGOs played a particularly strong role in monitoring campaign conditions during the 2012 election; and citizens verified their voter registration and participated in election-night verification…” (Carter Center Report, p.25).

Assessment

As we said in 2012, the electronic platform and mechanisms for expert and citizen audit that the CNE has put together over the past ten years are admirable. And polling consistently shows that the CNE has the highest positive evaluations of all of Venezuela’s public institutions.

However, its inability to ensure a fair campaign remains an issue. It undoubtedly realizes this as its public responses to criticism inevitably change the topic from campaign conditions towards the functioning of its electronic platform. Uninformed statements from US officials only help the CNE commit ignoratio elenchi.

Most important among these deficiencies are the failure to clearly distinguish when a public official is acting as a candidate and when as a holder of public office (which allows for the use of “cadenas” and public spending announcements as part of the campaign), the use of public resources for campaign purposes (such as vehicles for mobilization, banners on government buildings, government workers attending rallies, and the use of state media for partisan purposes) as well as limitations on advertising (which reduces the opposition candidates ability to get his message out).

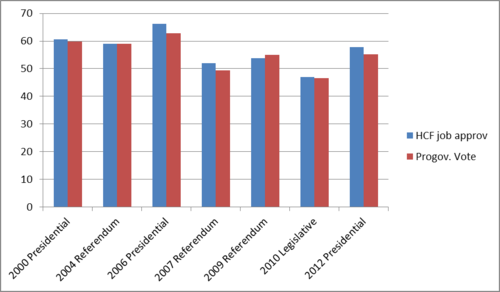

How important are these deficiencies? There is no easy answer. What can be said is that so far Venezuelan elections seem to be a fairly clear reflection of public sentiment. Figure 1 shows the numbers from Venezuela’s most reliable pollster during the Chavez period. It shows that the vote for Chavez was always within a couple of points of his favorability ratings in their last poll before the election. It further shows that the two elections that the Chávez government “lost”-the 2007 constitutional referendum and the 2010 legislative elections-were lost because Chávez’s popularity was near or below 50%.

Figure 1: Chavez Job Approval versus Pro-government Vote in Datanálisis Omnibus

This would suggest that election day dynamics such as unjust advantage in mobilization (because the PSUV might have information not available to the opposition with which they can pinpoint supporters who have not voted, or because they are using government vehicles to bring people to the polls) are not seriously distorting the expression of popular will. This is most likely because the opposition still enjoys an advantage in getting its message out since it has the sympathy of the private media and private media still has a large lead in viewership.

However, it does not tell us the impact of the other advantages of incumbency which could work by impacting popular sentiment itself, i.e. unfairly using public resources to increase approval of government candidates. Two things can be said here. First, Chávez’s approval ratings at election time were not radically different than when there were no elections. There were no dramatic peaks and valleys corresponding to elections, in part because elections were so frequent.

Second, the Chávez machine has been strong but not invincible. When the government did unpopular things and made unattractive offers, they lost. In 2007 they closed RCTV and put forward a radically changed and poorly justified revision of the constitution and were turned back. In 2010, they devalued the currency, never got a handle on electricity outages, and paid for it in the legislative elections. In these latter elections the opposition went forward with impressive unity and had a degree of party articulation (degree to which opposition supporters are articulated with opposition parties) that they have not been able to repeat since.

One of the most negative consequences of the CNE’s failure to ensure a fair playing field is that it serves as a sort of red herring for the opposition. Their long term tendency has been to explain their poor performance by pointing to problems with the electoral system. They would be better served by hitting the pavement, getting to know their country, and putting together a more attractive offer. Sucre mayor Carlos Ocariz has shown that such an approach can work–building an impressive coalition in what should be a pro-Chávez stonghold. But the reality is that approval and trust ratings of most opposition politicians have been dismal in recent years-Capriles went into the October elections with “trust” ratings in the mid-30s, ten to fifteen points behind Chávez.

However, it is clear that failure to counteract incumbent’s advantage and ventajismo will become even more important issues in the coming years as all indications are that elections in the post-Chávez era will become closer. Furthermore, with terms ending for the three most moderate rectors of the CNE ending this month, electoral conditions could get substantially worse.