Questions added to Datanálisis Omnibus poll, fieldwork May 18-25, 2016, N = 1000, error +/- 3%

One of the most disturbing policies the Maduro government has adopted during its three years has been the Operación Liberación del Pueblo. It amounts to militarized incursions into neighborhoods supposedly infiltrated by gangs and “paramilitaries” to detain criminals and “disassemble” (desmantelar) their networks. After the operation, the number of “delinquents” killed is announced as well as the number of people detained for investigation. (See our coverage over the past year here, here, here, and here).

In April Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Venezuelan human rights group Provea made public a report arguing that the OLP had caused 245 deaths in 2015, supposedly in confrontations. However, the best information suggests only 3 security agents were killed in the same operations. 14,000 individuals were detained in the process of OLP raids for further questioning. However, only 100 of them were ever charged for crimes. OLP actions were also involved in forced evictions and forced deportations that violated Venezuelan and international law.

There is no evidence that these types of military operations reduce crime in any way and there is good reason to think they do not. The best information suggests that the murder rate actually increased or stagnated from 2014 to 2015 after two years of decline (watch video of Andres Antillano’s recent analysis, especially starting at 7:00).

Actual gang leaders usually have significant networks into Venezuela’s security forces and find out about an impending OLP raid well ahead of time. They make themselves scarce and return once security forces have left or simply set up shop elsewhere. The most concrete impact of the OLP is that it pushes small scale criminal gangs to organize and articulate into larger, better armed gangs more able to confront security forces (see extended interview with Andres Antillano here. See my analysis of the increasing organization of crime here).

None of this matters much to public opinion as the OLP is the perfect spectacle for a population hungry for relief from the crime and delinquency that besiege them. The OLP fits with a cultural model of crime and policing that values episodic, violent shows of force aimed at punishing bad people, rather than the patrolling and structured interaction with communities characteristic of civilian policing.

Polling firm Datanálisis showed in September 2015, two months after it started, that the OLP had the support of about half of the people who knew what it was (about a third of the population had still never heard of it at that time).

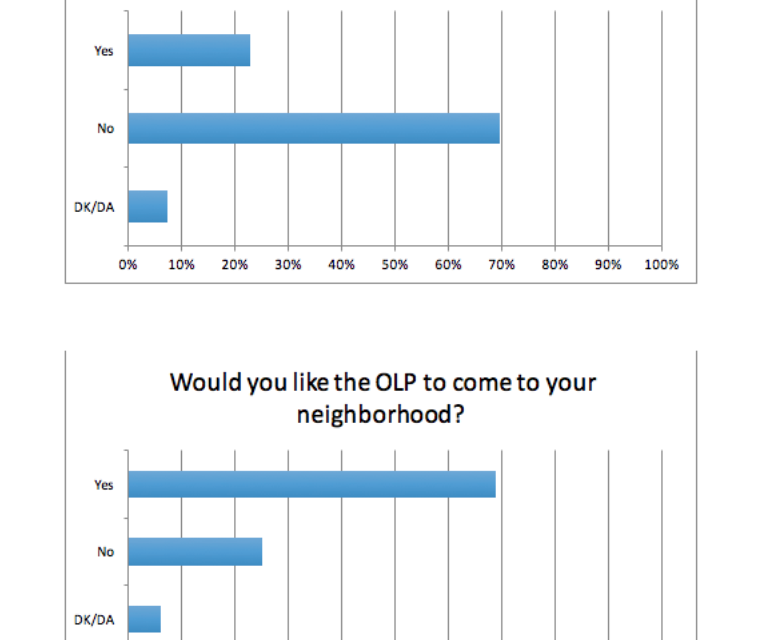

I wondered how much contact people actually had with the OLP, or whether it was really just restricted to media coverage. As well, I wondered whether it was the type of thing people liked, as long as it didn’t take place in their own backyard. In May I was able to add two questions to Datanálisis’ Omnibus poll. Respondents were asked whether the OLP had been to their neighborhood, and whether they would like it to come to their neighborhood.

The results were clear. While less than a quarter of respondents said the OLP had come to their neighborhood, over two thirds would like it to.

The next step would be to ask those people who say the OLP came to their neighborhood, whether it decreased crime and whether they would like it to come back.

These results are bad news for those of us who think Venezuela’s long tradition of militarized policing is one important cause of its problem with crime and violence. But the results are fully consistent with Rebecca Hanson’s and my finding that the military makes Venezuelans feel safer than civilian police forces.

The data certainly help us understand the failure of the 2008-2014 police reform which aimed precisely at creating a civilian police force. And they suggest that any future reform will need to start by generating public support for civilian policing.