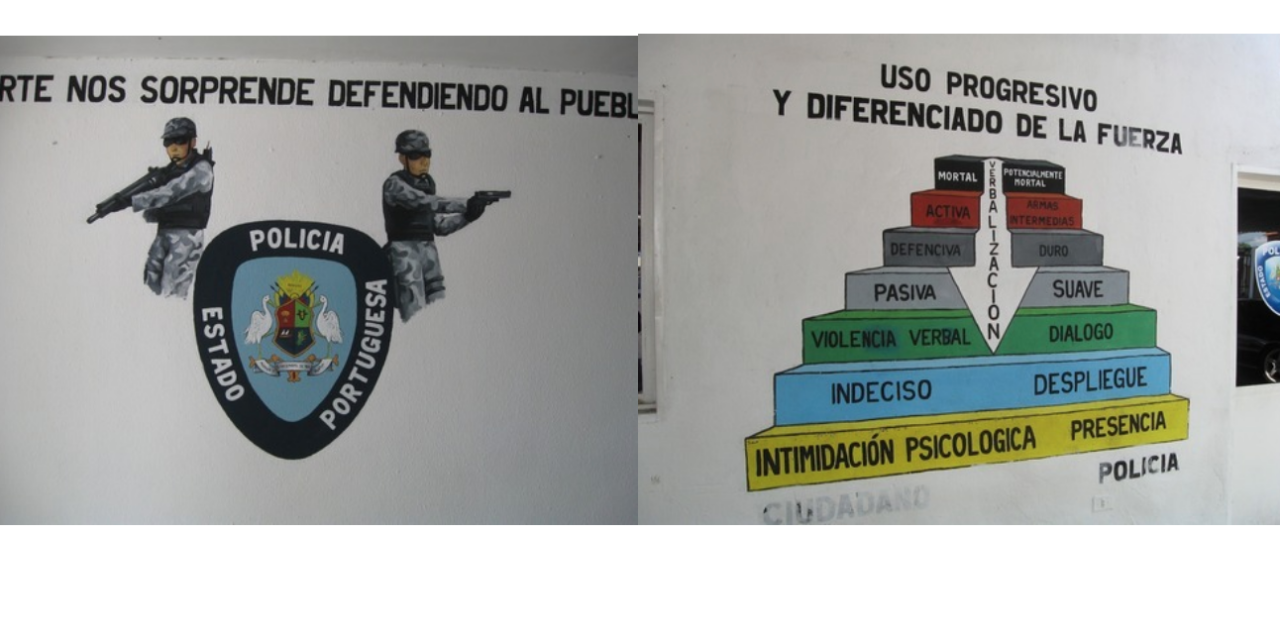

The two murals above adorn the walls of the police station of Portugesa’s state police force, succinctly capturing the current juxtaposition of two very different models of security in Venezuela. The first mural encapsulates well the traditional model of policing in the country, with its gun toting, special operations image of citizen security. The second mural, a much more recent image added to the station walls that is adapted from the General Police Council’s training manuals, symbolizes the move toward differential and progressive use of force, with an emphasis on dialogue rather than force as a primary response.

If “humanist-oriented” police reform in Venezuela is able to convince citizens, police officers, and politicians that security is not achieved exclusively by state use of violence, Venezuela could well turn into one of the most successful cases of progressive police reform in the region. However, this new model of citizen security—with its focus on prevention, citizen participation, and non-militarized policing—has a long way to go before it is accepted as the dominant approach to reducing crime and violence in the country.

Indeed, parallel to the police reform has been the creation in 2010 of the Dispositivo Bicentenario de Seguridad Ciudadana, or the DIBISE, an initiative run by the National Guard. The main tactics utilized by the DIBISE are security outposts and “alcabalas” (roadblocks) set up in high crime areas, which represent the same kind of “operativos” that the government has been using for decades. While this traditional military approach to citizen security has consistently shown itself to be ineffective, it does provide a visible state security presence in high crime areas.

These kinds of policing activities fulfilled by the National Guard and other military branches were heavily criticized by the CONAREPOL report (see previous post). Nevertheless, they continue to be popular with many citizens, as the militarized approach to security—though viewed as violent and repressive—is also often perceived as a necessary mano dura response to crime and insecurity. And it is the logical response for the National Guard which is part of the same Ministry of the Interior and Justice that is pushing forward the police reform. Many within the hierarchy of the National Guard have vested interests in the continuation of established routines, channels of authority and domains of influence and are not supportive of civilian police reform..

The tensions between these two models are highlighted by the change in the direction of the Ministry of Justice and the Interior from a civilian with a degree in criminology—Tarek El Aissami who left to run as the PSUV candidate for governor of Aragua, winning this post in December—to National Guard official Nestor Reverol. Indeed it was Reverol that designed the DIBISE as a parallel to the police reform. Given Reverol’s background these differences are easy to exaggerate. A closer look reveals that Reverol has been part of the design of citizen security reform from the beginning and has professed on numerous occasions a commitment to pushing forward the creation of a civilian police force. Nevertheless, many have wondered if the transition will mark a return to the predominance of military forms of policing in Venezuela

The DIBISE and approaches like it are not, however, the only challenges to police reform. As police scholars have long noted, both institutional culture and a lack of resources allocated to reform have tended to impede long-term changes in policing across the region. Additionally, the re-training of police officers at the municipal and state levels is still largely left up to the discretion of the directors of each police body. While conducting fieldwork, the first author has heard multiple CGP personnel telling stories of having visited police departments where CGP training guides and manuals were stacked up in closets, still in the wrapping they were shipped in.

The National Bolivarian Police (PNB, Policía Nacional Bolivariana) has also been criticized for not actually patrolling the “prioritized” (i.e. high crime) areas that they are charged with protecting. Rather, some maintain that PNB officers stick close to main streets and metro entrances, with some residents reporting that the new professionalized policemen “no suben cerro,” meaning they do not go into the dangerous barrios.

Another challenge to police reform is that some of the policies mandated by the reform have yet to be put into place. For example, many state and municipal officers will not see their pay increase until this year, as changes to pay have to wait to be factored into budgets for 2013. Given that poor pay is frequently cited as a main motivator of police corruption this could mean that one of the most important changes required by the reform will not even be implemented until this year.

Changing citizens’ perceptions of the new security model might perhaps be the most difficult obstacle the reform will face. While their emphasis on dialogue and progressive use of force cannot be overestimated, reformers’ advocacy of physical force as a last resort could produce an image of PNB officers as incapable of keeping citizens safe. For example, many of the residents in the lower-class sector where the first author conducts research refer to the PNB as a “soft” form of security, too soft to deal with violent areas of the city. As one woman recently expressed in a community meeting: Non-repressive policing is great but what good does dialogue do when a “delinquent” starts shooting?

Apart from references to the PNB as too “suave,” many citizens also describe PNB officers as too young (the 2008 Organic Law of the Police Service and of the National Police Body lowered the inscription age to 18 for prospective officers) and this youthfulness makes them wonder if the PNB are prepared for their jobs. As a teacher in Los Magallanes de Catia told the first author, these “little boys” are just recently hatched (“saliendo de la cáscara”). At the same community meeting mentioned above, a woman described PNB officers as scared of their own guns and unprepared to deal with “malandros” when they drew out their own weapons. UNES graduates actually receive more training than did their Metropolitan Police predecessors. However, these perceptions portray the PNB as a bunch of nice kids not yet ready to face the street.

This perception has only been heightened by the fact that the reform’s impacts on crime and violence are still unclear. According to statistics released by the CICPC (Cuerpo de Investigaciones Científicas, Penales y Criminalísticas), the homicide rate in Caracas fell in the first two years of police reform, from 122/100,000 residents in 2009, to 105 in 2010, and to 95 in 2011. For the country as a whole, the Ministry of Justice and the Interior calculated homicide rates per 100,000 residents as moving from 49 in 2009, to 45 in 2010, and 48 in 2011. Official rates for 2012 have yet to be released by the government.

However, according to the Venezuelan Violence Observatory (OVV, Observatorio Venezolano de Violencia), 2011 and 2012 were Venezuela’s most violent years ever. The OVV reported a homicide rate of 67/100,000 residents in 2011, with a rise to 73/100,000 residents for 2012. The OVV includes “deaths under investigation” in its statistic which leads to a higher overall rate than the CICPC. However what is important is the trend which worsened over a year’s time rather than improving. Calculating these numbers in Venezuela is tricky for a number of reasons (see a previous post by Robert Samet).

Of course, the impact of police reform is a complex issue since it cannot be expected to generate an immediate, direct and consistent reduction in crime. It also must be kept in mind, as this post has highlighted, that police reform is only part of the overall security strategy in the country–in addition to continued support for militarized intervention, little progress has been made in reforming the judicial or corrections systems. But in public policy perceptions are fundamental and citizens who continue to see homicide rates rise might favor a return to militarized policing strategies. In the end, consolidating the reform will require citizen and official support for a model of policing that does not define security as displays of power on street corners and arbitrary use of force against citizens.