In the first half of this year we ran a series describing Venezuela’s comprehensive efforts at citizen security reform. We have also traced the process over the past six months, whereby the civilian character of this reform has lost out in favor of militarized policing strategies. In the coming months we are going to run a series on public perceptions of citizen security in order to shed light on why reform has been so difficult to implement.

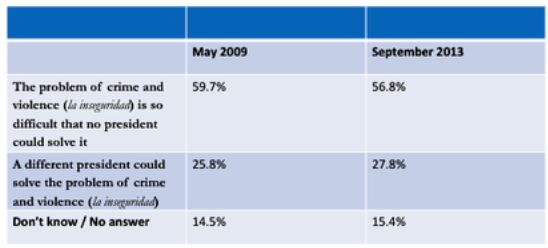

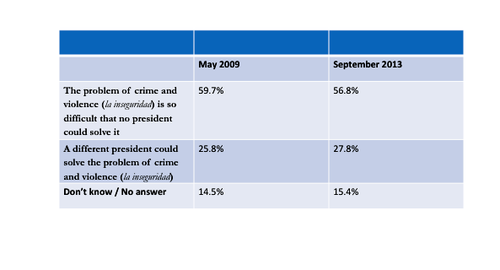

In March and April of this year, Nicolás Maduro made citizen security a campaign issue in a way that his predecessor never did. As we analyzed here, it was a somewhat risky strategy insofar as polls consistently showed that Hugo Chávez did not pay much of a political price for declining citizen security (we will unpack this phenomenon in a future post). Indeed, in 2009 a survey question asking about Hugo Chávez’s responsibility for crime found that almost 60% of respondents thought crime was such a difficult problem that no president could solve it. Only a little more than 25% thought that a different president would be more effective.

This was one of the reasons that it took the Chávez government so long to confront crime. It knew it did not pay politically for the issue and had no interest in altering this fact. Even when they began a comprehensive effort at citizen security reform in 2009, there was little public fanfare. Indeed it was not until January 2012 that Chávez publicly and forcefully addressed the issue by announcing Misión Seguridad.

In this piece we would like to ask whether the government increasingly “owns” the issue of citizen security in the eyes of the public. Put differently, have five years of citizen security reform and six months of Nicolás Maduro openly addressing the issue changed public perceptions? Is the government increasingly taking the blame for crime?

Incredibly, the data show very little has changed. We put the same question from 2009 mentioned above, on Datanalisis’ August-September 2013 Omnibus survey. The results were within the margin of error (x/-2.66%) and should be assumed to be identical.

After five years of civilian police reform, the creation of a new police university, the creation of a new police body, a presidential commission and a new law on gun control, a high profile presidential campaign in which the government candidate made citizen security his main issue, after a parallel militarized effort—the Bicentennial Security Dispositive starting in 2009, and the Plan Patria Segura starting this year—the majority of Venezuelans still see citizen security as an issue that is outside the scope of a President’s control.

Taking a step back it perhaps should not surprise us that perceptions have not changed. The same Datanalisis poll shows that 64.4% of respondents say that la inseguridad has worsened in the past year. Only 11.3% think it has improved. The average Venezuelan could rightfully think: “Even with all the efforts the government has made things have not gotten better. This problem simply goes beyond the government.”

But, if Venezuelans do not hold the President responsible for crime, whom do they blame for crime and violence? Another question we added gets at this. We had interviewers ask “Which of the following do you think are the primary causes of delinquency in Venezuela?”

The answers are striking and somewhat disturbing. The most common response is decline of the family with 27.8%. This response effectively privatizes the issue of crime, holding individuals and families responsible, rather than state institutions and actors.

“Police corruption” and “Deficient policing” together make up less than 10% of respondents’ answers (we will look at this issue in a future post). Ineffective government only gets 6.4%. The number two and three causes, lack of employment and ineffective government, are issues for which the Chávez government received relatively good marks from the population.

It should be pointed out that this question uses the term “delincuencia” instead of “la inseguridad.” While they are indeed synonyms in Spanish, it could be that for some people delinquency connotes youth crime instead of crime in general and thus responses referring to family, education and employment are overestimated. We hope to re-run this question in the near future, using the term la inseguridad.

Nevertheless, the results are striking and are certainly consistent with Table 1. Most people do not consider Venezuela’s crime problem to be the fault of the President. Neither do they see it primarily as the result of ineffective policing.

This sheds some light on why the opposition has been so unsuccessful in getting crime and violence to stick to Chávez and now Maduro in electoral contests. Perhaps more importantly it should assuage lingering fears within the governing coalition that if they robustly address the problem they will eventually be blamed for it. The data suggest that is not the case.

Unfortunately, the data also show why it is so difficult to generate political support for efforts at citizen security reform. For most people, citizen security reforms (reforming the police, cracking down on gun sales, etc.) are not the most obvious and convincing ways to address crime. In our next post we will discuss what citizens think can be done to reduce crime in the country.