Over the past two weeks, a familiar narrative has been resuscitated: the threat of “Islamic terrorism” emanating from Latin America, through the revival of one of its most important sub-narratives: the threat posed by Venezuelan authorities illegitimately granting passports to presumed terrorists in the Middle East. The allegations were included in the justification of a bipartisan letter calling on the Trump administration to expand the list of Venezuelan officials targeted for sanctions under the 2014 Venezuela Defense of Human Rights Act. But they were scaled up in importance by a prime time, two-part CNN report last week.

The renewed attention comes in the first month of a new presidential administration that has included securing U.S. borders and preventing terrorism in its platform, and many in Washington’s policy circles are hoping these allegations will become a priority. In the CNN investigation, for example, Roger Noriega dramatically argues: “I absolutely believe, and I state it so publicly, that if we do not get our arms around this problem, people are going to die.”

In this post we look at the evidence that has been marshalled in support of these claims. By any standards it is thin.

Bipartisan Letter from 34 Legislators Calling for Sanctions

The theme was revived as part of a recent bi-partisan congressional letter to the Trump administration. On February 8, Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL) and Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ) authored a letter, also signed by 32 other members of Congress, calling on the Trump administration to use its authority to impose further sanctions against corrupt authorities in the Venezuelan government. Much of the letter focused on Venezuelan military officials linked to appalling corruption in food distribution, and on evidence of Vice President Tareck El Aissami’s participation in drug trafficking. In addition, the letter raised allegations that El Aissami has ties to Hezbollah and Hamas and has been involved in providing passports to them and others in the Middle East.

To back up the latter assertions, the letter cites “media reports” from the American Interest and the Wall Street Journal. Upon closer inspection, however, these are not journalistic investigations that present actual evidence. The first is actually a transcript of verbal comments given by former New York District Attorney Robert Morgenthau in 2009. The second is actually a 2014 op-ed by commentator Mary Anastasia O’Grady.

The source of the Morgenthau piece is unclear, but in it he simply states that El Aissami is “suspected of having issued passports to members of Hamas and Hezbollah.” O’Grady’s op-ed cites a paper published in June 2014 by the Center for a Secure Free Society (SFS). According to O’Grady, the SFS paper asserts that, in the course of his duties in the Ministry of the Interior, “El Aissami’s office used information technology developed by Cuban state security to give some 173 individuals from the Middle East new Venezuelan identities that are extremely difficult to trace.”

However, when we look at the actual SFS paper cited by O’Grady, “Canada on Guard: Assessing the Immigration Security Threat of Iran, Venezuela and Cuba,” the only actual evidence it cites is an “estimate” from unnamed “regional intelligence officials” that 173 “individuals from the Middle East were provided passports and national ID cards in Venezuela from the period of April 2008 to November 2012, overlapping the tenure of Tareck El Aissami” as Minister of the Interior.

CNN’s “Passports in the Shadows”

On February 8, CNN began broadcasting a two-part investigation called “Passports in the Shadows” on AC360° and CNN en Español that further explored allegations that diplomatic authorities sold Venezuelan passports to individuals who may have had links to terrorist organizations in the Middle East. In apparent retaliation, the Venezuelan government took CNN en Español off the airwaves in Venezuela, a clear act of censorship.

The primary source for part one of the investigation is Misael Lopez, a former employee of the Venezuelan Embassy in Iraq from July 2013 to July 2015, who has since sought political asylum in Spain. Lopez claimed and showed evidence that Venezuelan visas and passports were irregularly sold out of the embassy to citizens of Iraq, Syria, and other Middle Eastern countries. He appears to have first made these allegations to Venezuelan journalist Andreina Flores in November 2015, and they subsequently gained steam in English on Breitbart News.

Lopez’s claims seem plausible and are a cause for concern. But they should also be understood in context.

First, passport fraud is a long standing security issue and not in any way limited to Venezuela. There have been reports of similar schemes being run by corrupted officials in Guatemala, Belize, and elsewhere. Some have even spoken of an “epidemic” of false European Union passports.

Second, to enter the United States, Venezuelan citizens need not only a valid passport but a valid visa. Hence, entry of an individual with a false Venezuelan passport would require a serious lapse of the U.S. government’s own immigration system.

The second part of the CNN investigation interviews Marco Ferreira, a retired Venezuelan brigadier general who sought exile in the United States after participating in the 2002 coup attempt against President Hugo Chávez. Ferreira, who headed Venezuela’s Department of Identification and Immigration between 2001 and 2002, found evidence of irregularities in the system, including “suspected drug traffickers and terrorist groups” with Venezuelan passports. Even setting aside the likely biases of a military officer who tried to overthrow the Chávez government, it is unclear how relevant 15-year old allegations are. If such passports were being used by terrorists, we would presumably have known about it by now. What is more, any passports given out in 2002 or before would have expired years ago.

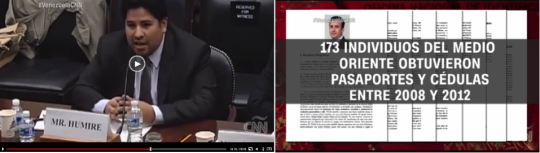

Finally, the CNN investigation cites what it calls a “confidential intelligence document” said to link El Aissami to “173 Venezuelan passports and ID’s that were issued to individuals from the Middle East, including people connected to the terrorist group Hezbollah.” If that number seems familiar, that is because it is the same figure in the 2014 Center for a Secure Free Society (SFS) paper mentioned above. CNN does not cite the source of this “confidential” document, but the CNN en Español version of the story claims that the information was “presented to Congress in 2015” and displays an image of SFS Executive Director Joseph Humire testifying before lawmakers (see image below).

Summary of the Evidence

The evidence being presented in this new effort to argue that Venezuelan passports are being provided to terrorists is the following:

- Statements from Robert Morgenthau from a verbal presentation, themselves citing no publicly available evidence.

- A much recycled SFS paper citing unspecified “regional intelligence officers.”

- The statements of a former Venezuelan military officer involved in an attempted coup against the Chavez government 15 years ago about passports that have long-since expired.

- Evidence presented by a former Venezuelan Embassy official in Iraq.

Of the four sources, the last seems the most credible. Yet looked at in context, it does not justify the dramatic claims it has been used for. Passport falsification is not unique to Venezuela and in any case the difficulty of obtaining a U.S. visa means the potential for any implicit security threat to the United States is extremely low.

None of this undermines claims that El Aissami has ties to drug trafficking or to Hezbollah and Hamas—claims that should be investigated and weighed with evidence. But the idea that there are Venezuelan passports floating around the globe providing terrorists with an opportunity appears to be a tempest in a teapot.

As Chris Sabatini has suggested, the recent uptick of salacious claims regarding a terror threat emanating from the region is in part due to officials seeking the attention of the Trump Administration as it settles in. Linking Venezuela to a supposed terror threat emanating from the region has long been a key goal of sectors seeking U.S. intervention and given Washington’s new “normal,” it is perhaps not surprising that the story has gained legs again. By linking Venezuela to terror, stakeholders seek to make a nuisance and human rights crisis into a national security threat, and thereby generate the action they seek.